Olympic torch 2012 as it passes through Penicuik

Liddell on way to a win

|

| | | Eric Liddell Olympic Champion and Missionary |

The

service on Sunday 10th June took Eric Liddell as the theme. The

Sunday School children, who have been studying the life of Eric Liddell

took a baton that Sandy Robertson had brought with him, round the

church aisles in a relay. The

service on Sunday 10th June took Eric Liddell as the theme. The

Sunday School children, who have been studying the life of Eric Liddell

took a baton that Sandy Robertson had brought with him, round the

church aisles in a relay.

Sandy then told us the story of Eric Liddell's olympic and religious life, see below.

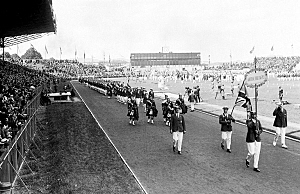

Paris, 1924- six years after the end of the First World War. The band of the second  battalion,

the Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders is swinging down the Champs

Elysees towards the tomb of the Unknown Warrior with the Olympic teams

in tow, because Paris in 1924 is hosting the Olympic Games at Colombes

stadium. As the wreath is laid and the minute’s silence observed,

many of the athletes are thinking of their comrades slain in the recent

conflict; one man, a Scotsman in the G.B. team, may well be thinking of

his fellow-countryman, Wyndham Halswelle, Olympic 400mLiddell o way to a win

Champion in London in 1908, whose life was cut short by a

sniper’s bullet in the trenches of Neuve Chappelle; the man is

Eric Liddell from Edinburgh, and his ambition is to emulate his

compatriot’s feat of winning the Olympic quarter

mile. battalion,

the Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders is swinging down the Champs

Elysees towards the tomb of the Unknown Warrior with the Olympic teams

in tow, because Paris in 1924 is hosting the Olympic Games at Colombes

stadium. As the wreath is laid and the minute’s silence observed,

many of the athletes are thinking of their comrades slain in the recent

conflict; one man, a Scotsman in the G.B. team, may well be thinking of

his fellow-countryman, Wyndham Halswelle, Olympic 400mLiddell o way to a win

Champion in London in 1908, whose life was cut short by a

sniper’s bullet in the trenches of Neuve Chappelle; the man is

Eric Liddell from Edinburgh, and his ambition is to emulate his

compatriot’s feat of winning the Olympic quarter

mile.

The quarter is considered to be a man- killer, an

event for the ancient Stoics, impervious to pain, an event where high

blood acidity must be tolerated during the latter stages of the race.

Eric

Liddell, Scottish Rugby winger and international sprinter, winner of

the British 100m and 200m titles, and a committed Christian, has a

simple answer for anyone who asks him about his 400m racing

tactics,

‘I run the first 200 as fast as I can…then,

for the second 200, with God’s help, I run harder.’

I’ll second that.

Live a life that measures up to the standard God set when he called you:

Most

people know the story of Eric Liddell’s Sunday Observance.

However, license was used in the film, ‘Chariots of

Fire’ because rather than making a last minute decision,

Liddell was able to decide in January 1924 when the Olympic

programme was announced; told, in an effort to dissuade

him, that the continental Sunday finished at midday, Liddell replied,

‘My Sunday lasts all day’. Most

people know the story of Eric Liddell’s Sunday Observance.

However, license was used in the film, ‘Chariots of

Fire’ because rather than making a last minute decision,

Liddell was able to decide in January 1924 when the Olympic

programme was announced; told, in an effort to dissuade

him, that the continental Sunday finished at midday, Liddell replied,

‘My Sunday lasts all day’.

Eric lined up in

the outside lane, used his trowel to dig his starting holes [in the

days before blocks], and shook the hands of his five rivals. There

being no live television transmission, and times being more

arbitrary, the pipe major of the Queen’s Own Cameron

Highlanders, recently seen on the Champs Elysees, had time to call to

his fellow-countrymen,

‘Let’s gie the lad a blaw’, and the band responded with alacrity with ‘The Campbells are coming’.

The

story of Eric Liddell’s Sabbatarian principles were well

known; he would not run on a Sunday, the day set aside by God; as a

result, he would not run the Olympic 100m, won by his inferior, the

Englishman Harold Abrahams.

The G.B team had trainers and

physios; one of them, sympathetic to Liddell’s principles, had

handed him a paraphrased text from First Samuel 2: 30 as he went out to

run:-

“As the old book says, ‘he who honours me, him will I honour’”.

Offer yourselves as a living sacrifice to God, dedicated to his service:

From

the outside lane, in a less than familiar event, but a thrilling

Olympic final, Eric Liddell, the Flying Scotsman, won the Olympic gold

medal in a new World record- he had run the first half fast as fast as

he could, and then, with God’s help, he had run the second half

faster -he had honoured God in his own way, and God had honoured him. From

the outside lane, in a less than familiar event, but a thrilling

Olympic final, Eric Liddell, the Flying Scotsman, won the Olympic gold

medal in a new World record- he had run the first half fast as fast as

he could, and then, with God’s help, he had run the second half

faster -he had honoured God in his own way, and God had honoured him.

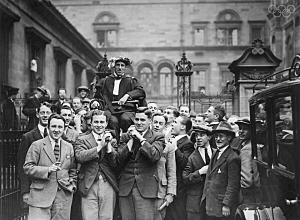

Next

day, the Sunday, he honoured God again by preaching the sermon at the

Scots Kirk in Paris – his text was ‘they were swifter than

eagles, they were stronger than lions’- and he returned to

Waverly station in Edinburgh to an adoring throng -the station

was mobbed. Six days later, as he graduated B.Sc. from Edinburgh

University, his principal quipped, ‘You have shown that none can

pass you but the examiner’.

Eric spent a year at Divinity

College, and when he preached, the churches were packed, with

congregations squeezing onto the pulpit steps to hear him. His career

seemed set- and what was that career?

Was it parish ministry?

No- he was to follow his father, and his brother Rob, in working for the London Missionary Society in China.

When

he left Waverly Station, it was again packed, as it had been for his

Olympic ovation. An eyewitness reported that Liddell himself started

Hymn 470: Jesus shall reign where’er the sun does its successive

journeys run.

The Mission Field, Tientsin:

Eric

travelled by the Trans-Siberian Railway to Tientsin in Northern China.

There he raised funds for a running track considered one of the finest

tracks in Asia, but this was only a small part of his great legacy in

the mission field. Eric

travelled by the Trans-Siberian Railway to Tientsin in Northern China.

There he raised funds for a running track considered one of the finest

tracks in Asia, but this was only a small part of his great legacy in

the mission field.

When China was invaded, and Britons

interned after the Sino-Japanese war, Liddell was among them. Having

sent his pregnant wife and two daughters to safety in Canada, he set

about becoming a teacher in the camp.

To stop the children

fighting, he refereed hockey matches, mending the hockey sticks with

fish glue during the night; he made baseballs from scraps of curtains

and sheets; all in all, he became a surrogate father to many children

in the camp, and was universally loved.

He twice refused

repatriation; he firstly gave his place up to an expectant mother; you

may be surprised to hear secondly that Sir Winston Churchill himself

attempted to broker Eric’s release.

And it’s

not a happy ending - Eric Liddell died in the camp in February 1945 of

a brain tumour; the children he had nurtured in the camp became his

cord bearers when he was buried beneath the snow in northern China, his

grave marked by a simple wooden cross, his name spelt out in boot

polish.

For 45 years Liddell’s grave lay unknown; then it

was moved to the Mausoleum of Martyrs southwest of Beijing to the last

resting place of those considered to have given their lives for China.

Few foreigners, and even fewer Christians, have been accorded such an

honour in Communist China.

There’s a post-script: Allan

Wells, the new Flying Scot, when interviewed by the BBC in 1980 after

winning the Olympic 100m in Moscow, was asked, ‘Were you thinking

of Harold Abrahams as you crossed the line?’ My old team

mate, always quick on his feet, replied, to the delight of the entire

Scottish Athletics community,

‘No, I was thinking of Eric Liddell, actually’.

Allan

Wells, a Boys’ Brigader to his bone marrow, was familiar with

John Keddie’s stories of Eric. Dr. Stephanie Cook of Ayrshire,

the Olympic Modern Pentathlon Champion, when still a

cross-country runner at Oxford, was given a copy of Sally

Magnusson’s Eric Liddell biography inscribed, ‘To the

Flying Scotswoman’.

At the Sydney Olympics, lying in eighth

place after the swimming, shooting, fencing and show jumping, she won

the gold with a brilliant cross-country run.

A year later she added the world title, and promptly retired.

Two

days later Dr Cook flew to ravaged Gujarat with Merlin, the medical

charity – her inspiration, she said, had been Eric Liddell; and

like him she had chosen a life of service to her Lord and Master.

It’s quite a thought, and quite a legacy.

Back to Top

| |